There have been a number of reviews of Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget, but none that I have come across has included a bibliographic note specifying or describing the physical aspect of the reviewed copy. So I’m going to buck the trend and declare outright that I’m about to review the 2010 Allen Lane paperback edition of the book, which differs from others released in other countries and looks like this.

You can probably see already why I’ve made this distinction. I’m going to further allow you to visualise this object noting the power, headphones and USB ports on its spine,

as well as the fact that the ISBN and barcode are printed on a product badge such as those commonly found on consumer electronics products.

Finally, turning back to the front cover, I will note that the book appears to be switched on.

You can imagine it sitting on a bookshelf after you’re done with it, quietly humming away, its battery slowly depleting. Of course we have encountered buzzing books made of paper before. This is nothing new. But the idea implicit in the design is that the contents of the book might some day become exhausted, and cease to have human meaning, reverting to recyclable inert matter or mute space-filler. Which stands to reason, if you think about the speed at which (some) books about the internet become obsolete. But surely Lanier hopes for his invective to last longer than that – at least as long as one of Neil Postman’s would be my guess. So why did he approve this preposterous design? I’m going to have to come back to this later in the review.

I should also state outright that I wanted this book to be better, but I’ll take what I can get because I am strongly convinced that we need more books like this: popular, accessible critiques of digital ideology, written engagingly by somebody who knows his way around the technology and the culture. And while You Are Not a Gadget is weak at times – notably in its apparent inability to conceive of the political – it also contains a number of valuable and challenging statements, roughly defined as ‘the ones that I agree with’.

You Are Not a Gadget’s main contention is that web 2.0 is undoing the progress of the first stage of the World Wide Web, reducing personhood and expression by imposing an ever narrowing range of social and knowledge templates and the corporatist logic of companies like Facebook and Google. These developments, Lanier tells us, are consistent with the ‘cybernetic totalism’ espoused by many key players in Silicon Valley, according to which the internet (or, if you prefer, the hive mind that is coextensive with it in Lanier’s analysis) is about to achieve autonomous sentience, if it hasn’t already, and at any rate it is an entity greater, wiser and no less worthy of rights than the sum of its parts – which is to say, us.

By way of example of how self, meaning and expression are reduced as a result of this totalism and the deployment of its preferred technologies and designs, Lanier cites amongst other things the process of identity construction via a series of drop-down menus involved in creating a Facebook account, the ‘lock-in’ of MIDI as the standard for encoding music digitally– in spite of its inability to adequately represent the world of sound in the gaps between its discrete steps – and, most importantly of all, the process whereby experience is transformed (alienated) into information, and yet that information is regarded as functionally equivalent to experience. You might recall me making a similar argument on this blog from time to time: namely, that by eliding the difference between computer memory and the particular subset of knowledge that is made up of personal, collective and historical memory, digital ideology is claiming guardianship over one of the most fundamental aspects of social communication; and furthermore, insofar as memory plays a significant role in defining personhood, that this move creates a pattern of exclusion whereby only the people whose recorded experiences are compatible with the principal digital formats get to remember stuff and be remembered themselves.

It is in order to highlight those particular fissures that I wrote firstly my dissertation and secondly this blog, so obviously Lanier gets no quarrel from me on those particular points. But some of you may also recall my advocating from time to time a gentle resistance to certain biases of the medium – such as the ease of posting in blogger platforms which encourages instant commenting, or the pressure to speak quickly and often on Twitter – and here too I was pleased to see the author advise similar strategies. To wit, from a longer list on page 21:

- Post a video once in a while that took you one hundred times more time to create than it takes to view.

- Write a blog post that took weeks of reflection before you heard the inner voice that needed to come out.

- If you are twittering, innovate in order to find a way to describe your internal state instead of trivial external events, to avoid the creeping danger of believing that objectively described events define you, as they would define a machine.

These hints may seem a little facile, if not downright paternalistic – I believe I can in fact almost physically hear some of you cringing – but I think that they have some validity if for no other reason that I have personally found them of use. Not being much of a coder, and a relatively late adopter to boot, I have benefited significantly from the great immediacy and usability of web 2.0 tools, including, yes, Blogger, Twitter, Facebook and Wikipedia, each of which undeniably has its uses, but I’ve also been wary as many people are of how collectively they construct us as subjects. Pushing back, or as Lanier puts it ‘resist[ing] the easy grooves they guide you into’ (22), involves developing valuable forms of discipline and has the added benefit of denaturalising the medium, rather than continuing to operate under the very tempting assumption that its way of doing things is the only way of doing things. That is what Lanier means by lock-in, of which the file as a unit of meaningful information is perhaps the most apt example: there could be – or perhaps could have been, at this late stage – operating systems not based on the manipulation of files, and the difference could well affect substantively the way we conceptualise information itself. But the file is simply all there is, and it’s hard to even imagine an alternative.

The targets of Lanier’s critique that are likely to cause the most surprise amongst people not familiar with his work as a columnist are Wikipedia, the open culture/Creative Commons world, the Linux community and the vast majority of peer-to-peer filesharing, all of which are variously charged with advocating the erasure of context, authorship and point of view, thus pureeing us into the hive mind. The case of Wikipedia, for which Lanier evokes the idea of the Oracle Illusion, ‘in which knowledge of the human authorship of a text is suppressed in order to give the text superhuman validity’ (32), is a fine example of how a useful tool becomes all that there is simply by virtue of its extraordinary convenience. And the section on file-sharing and the business models of journalism and the creative industries, while punctuated with some questionable statements, nonetheless makes at least one challenging point:

If you want to know what's really going on in a society or ideology, follow the money. If money is flowing to advertising instead of musicians, journalists, and artists, then a society is more concerned with manipulation than truth or beauty. […] The combination of hive mind and advertising has resulted in a new kind of social contract. The basic idea of this contract is that authors, journalists, musicians, and artists are encouraged to treat the fruits of their intellects and imaginations as fragments to be given without pay to the hive mind. Reciprocity takes the form of self-promotion. Culture is to become precisely nothing but advertising. [83]

I tried to tease out some aspects of this last week with regard to the experience of seeing a particular post from this blog liked, linked and shared by others, and suggested that these actions can also be a form of appropriation, compensated with the universal currency of reputation-enhancing promotion. Rather more bleakly, Lanier claims in the preface that the reactions to his book ‘will repeatedly degenerate into mindless chains of anonymous insults and inarticulate controversies’ (ix), implying that his argument will be not only appropriated but in fact picked apart and perverted, and nothing good will come of the encounter of the book with the hive mind.

This however is quite problematic. For all of his readiness to dismiss internet forums as a viable vehicle of debate and the exchange of ideas, Lanier doesn’t argue convincingly or in fact at all that conversations in other media and contexts are any more productive, which situates the book in a perplexing rhetorical vacuum. Who exactly is Lanier trying to persuade, and how?

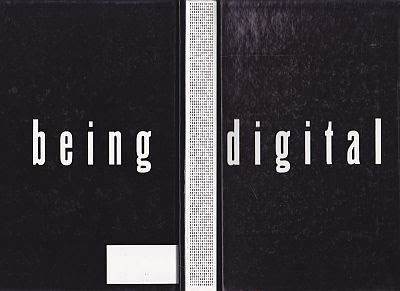

Failure to reflect not only on print as a medium, but on the recourse to print for this particular critical work at this particular time, weakens Lanier’s position. After all, one could contend that books are also carriers of information that is alienated experience, and that most of them are just as impoverished from a design point of view and suffering from at least as many lock-ins – such as (for us) the Latin script, or the length under which a book fails to qualify as a proper book – as your average template-based blog or social web platform. In fact, as I noted above, this particular book is available in many different editions with a number of different covers and graphic presentations, but reviewers don’t bother to mention this because they regard the form as being immaterial to the content. I happen to think that they are wrong. In replicating the appearance of an early Sony eBook reader, the Australian paperback edition of You Are Not a Gadget undercuts in fact Lanier’s critique. There is nothing ironic about the navigation buttons and the communication ports; on the contrary, it is precisely the kind of mashup of forms that the author finds so lamentable and ubiquitous a feature of web 2.0. Even more unfortunate was the decision to blanket the third and fifth page in the book, before Lanier gets down to business, with a sequence of binary digits. Not just because of how unimaginative it is, or how pointedly (albeit, I must assume, unwittingly) it underscores the author’s preoccupation – expressed in the preface – that his words will be mostly read by robots and algorithms; but primarily because of the echoes with the spine of Nicholas Negroponte’s Being Digital.

I cannot think of a single book as profoundly antithetical to Lanier’s philosophy as this one, which is all about embracing our future as creatures of bits and insisting that we are, in fact, gadgets, or a thinker as unsympathetic to his cause as Nicholas Negroponte, who thinks that possessing a laptop with which to connect to the hive mind is the key to the emancipation of the world’s poor. Yet the fact that the two books are so similar in appearance cannot be written off as a coincidence, but points rather to the aspects of our old media that we have become blind to, and how this blindness prevents us from fully comprehending and mobilising their capacity for persuasion.

And so what disappoints about You Are Not a Gadget is its insufficient appreciation of the texture not just of the media themselves, but of our being social. Dismissing the web’s prodigious capacity to share and disseminate texts – which is to say, value them – as the reciprocity of self-promotion, is ultimately as reductive and deterministic as the narrow conceptual frameworks that Lanier exposes in his book. And the same goes for creativity. As this recent example from Whitney Trettien’s excellent blog illustrates, historians of the book occasionally delight in reminding us of the strangeness that was lost as the medium became more and more standardised in the name of cost-effectiveness and efficiency – we should strive to recapture it, and not just on our computers.

Jaron Lanier. You Are Not a Gadget. Sydney: Allen Lane, 2010.